Yves here. As Hubert Horan has explained from the outset of his series on Uber, the gig worker company has an inherently higher cost structure than traditional taxi companies. Yet it’s managed to con investors and an uninquisitive financial press into believing that attaching an app to a taxi service somehow magically creates scale economies.

Uber’s pricing advantage was illusory, the product of enormous investor subsidies. We predicted that Uber would eventually have to raise prices to a higher level than traditional taxis to cover its operating costs and attempt to provide an adequate return on the massive funding of losses. That is starting to happen.

But as we also pointed out, taxi services have low barriers to entry. Expect Uber’s market share to erode as at least some riders reject the price gouging. Yet even at these higher fares, Uber is still losing money.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

Uber Released Its Second Quarter 2022 results on Tuesday August 2nd.

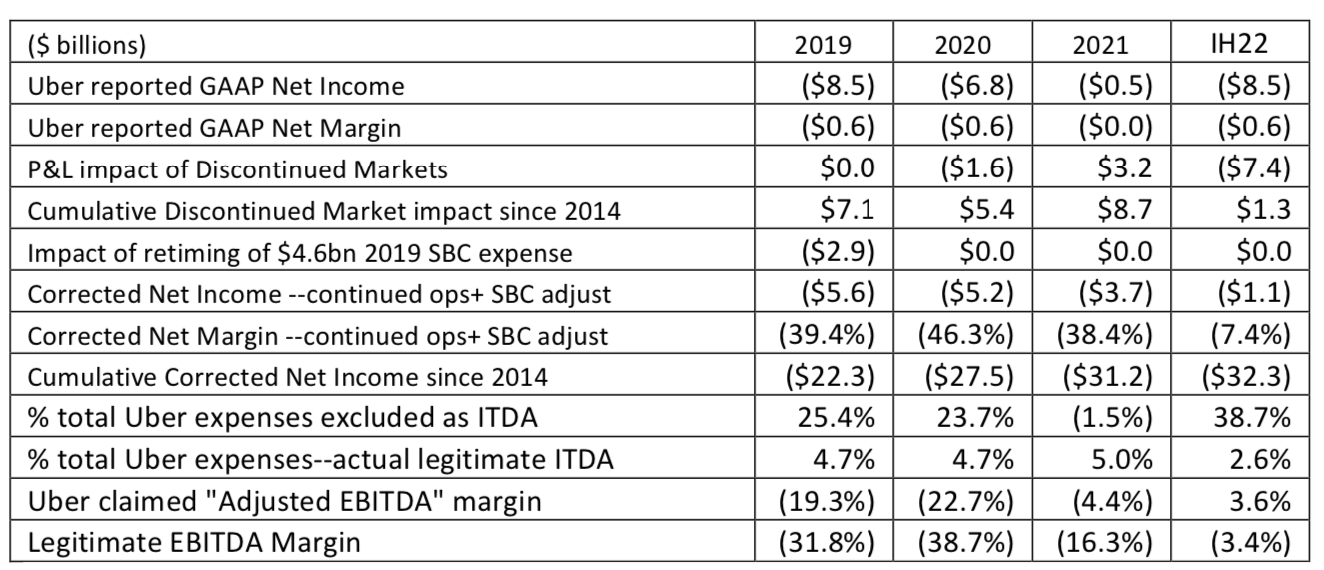

Uber’s GAAP Net Income from ongoing operations was negative $1.1 billion in the first half of 2022, bringing its cumulative GAAP losses to $32.3 billion.

As has been discussed on multiple occasions in this series, Uber deliberately makes it very difficult for investors or other outsiders to understand current financial performance and trends.

Two ongoing accounting problems are Uber’s deliberate comingling of results from active/ongoing and failed/discontinued operations and its emphasis on a bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” which does not measure either EBITDA or Profitability and provides no meaningful information about changes in Uber’s financial performance. As a result this series has always compared Uber’s published results with properly stated results limited to ongoing operations and with legitimate measures of EBITDA. [1]

Legitimate EBITDA is GAAP Net Income minus interest, tax, depreciation and amortization expense. Since 2015, these have typically accounted for less than 5% of Uber’s total expense. The expenses Uber excludes from Net Income to produce its bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” measure often account for a quarter of Uber’s total expenses, and in the first half of 2022 accounted for over 38%. There is nothing wrong with including an EBITDA number in financial reports but misstating it by $8 billion is a different matter. This misstatement allows Uber to mislead gullible investors and journalists into thinking that it is now “Profitable”. Actual EBITDA in the second quaretr of 2022 was negative 3.4%, not the positive 3.6% it has been ballyhooing. [2]

In most cases, when Uber shut down a failed operation, such as its autonomous car development unit, or major operations in markets such as China, Russia and Southeast Asia, the operator that had driven Uber out of the market gave Uber some non-tradeable securities in return for exiting the market faster. In 2016, 2018 and 2021, Uber inflated its profitability by a combined $12 billion, based on its (unverifiable) claim as to how much those securities (in companies that had never generated any profits) had appreciated.

Because Uber wanted to juice published earnings prior to its IPO and in the depts of the pandemic, it had to maintain the fiction that these securities were “investments” Uber had pursued as one of its core strategies for generating shareholder returns. In addition to misleading investors about its actual 2016, 2018 and 2021 financial performance, this practice produced wild, inexplicable year-to-year fluctuations in bottom-line profit numbers, making it impossible for outsiders to understand actual underlying trends in financial performance over time. [3]

Why Hasn’t Uber Tried To Explain Clearly the Reasons for the Big Reduction in Uber Losses?

While Uber is still far from breakeven, the recent improvements in financial performance were highly significant. As will be discussed below, total revenues now exceed pre-pandemic levels, its Net Margin has improved from negative 40% in 2019 to negative 11%, and in its thirteenth year of operations it finally produced its first dollar of positive cash flow.

But Uber’s recent financial release made no attempt to explain exactly what Uber did to achieve these improvements, and as a result none of the news stories about Uber’s second quarter results could tell readers what explained the big changes or whether they had any potential to drive ongoing profit improvements.

In addition to using bogus EBITDA “profitability” numbers and conflating numbers from ongoing and discontinued markets, Uber’s financial reports never included the critical data other large public companies routinely report that would allow outsiders to understand P&L changes. It is impossible to tell whether revenue changes are volume or pricing driven. It is impossible to understand the relative impact of rides and delivery service on profit shifts, or the relative profit performance of Uber’s different geographic markets. Uber’s reports provide no information about efficiency gains and no unit cost data below the aggregate international corporate level.

Prior to the pandemic this was because Uber never wanted its investors, drivers or the cities it served to understand how horrible its economics were, and that its extremely rapid growth was not going to produce sustainable profits. During the pandemic Uber never wanted its investors, drivers or the cities it served to understand how devasting the demand collapse had been. Companies that had developed strong business models with proven ability to drive profitable growth proactively worked to educate the investment community about the drivers of their competitive and financial strength. Uber relied instead on a constantly changing set of artificial narratives, knowing that a pliant business press would never critically scrutinize them.

Perversely, Uber’s longstanding non-communication/miscommunication practices have prevented outsiders from understanding that it has recently achieved major, substantive improvements. Because it used paper gains from untradeable securities to misstate the results of current performance in past years, it was forced to publish current financial results much worse than its underlying current performance warranted. Its official GAAP Net Income was negative $8.5 billion, but $7.4 billion of this was from the paper losses on these securities. If properly limited to ongoing operations, Uber lost “only” $1.1 billion in the first six months of this year but news reports emphasized the horrible official losses. Since Uber had never helped reporters understand their underlying economics, they could see that “revenue was up” but had no way of understanding what had caused it, or how significant it was. [4]

As Uber’s results improve it would be nice to be able to analyze how much was due to gains in ridesharing versus delivery, and to have enough detail to evaluate whether the recent growth was just a one-time rebound from depressed pandemic levels or resulted from underlying improvements that might continue into the future. But Uber does not want investors, journalists, drivers or the cities it serves to establish an independent ability to understand what drives its profit performance. It doesn’t even break down the trip data needed for any analysis of unit costs and unit revenues below the aggregate grand total. But the crappy data Uber does publish provides some very powerful clues.

Uber’s Big Recent Gains Were Driven by Huge Fare Increases and Driver Compensation Cramdowns That Transferred Billions from Drivers to Shareholders.

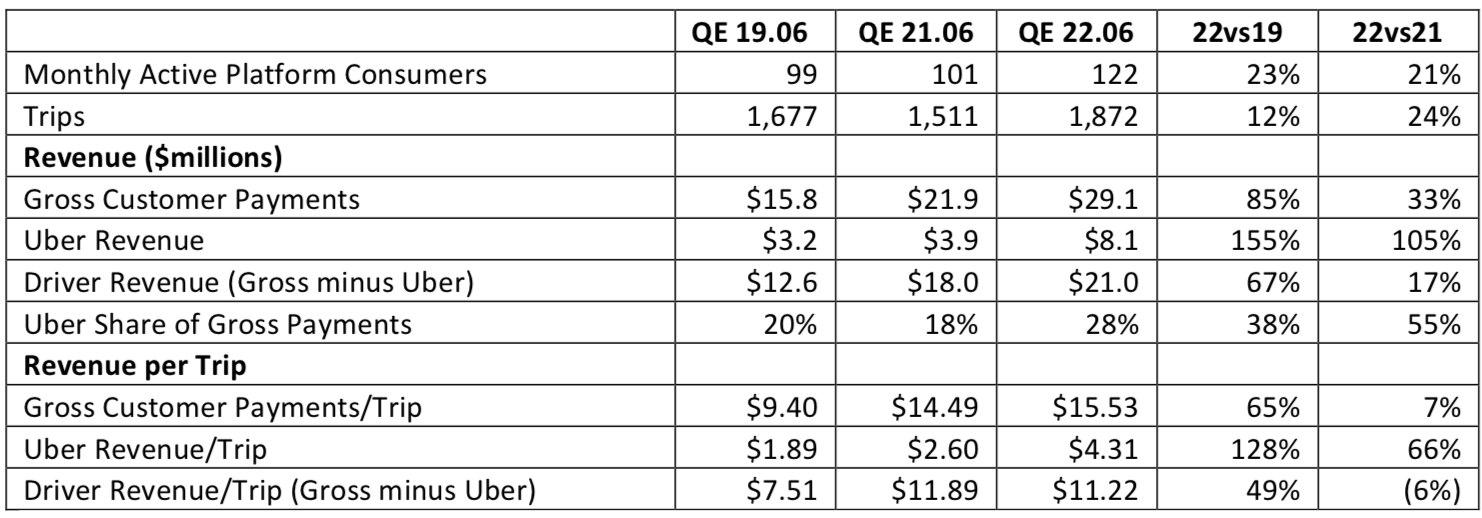

The table below compares the limited revenue and unit revenue data Uber discloses for the second quarter of 2022 to the comparable quarters of last year and 2019.

Revenues are already significantly higher than their pre-pandemic peaks, driven by price increases that were largely in place by the summer of 2021. Versus 2Q19, gross customer payments per trip were 54% higher in 2Q21 and 65% higher in 2Q22. Total gross customer payments increased $13.3 billion per quarter ($29.1bn minus $15.8bn). Assuming 12% of this increase is due to the higher trip volumes, this implies that Uber extracted $11.7 billion more out the marketplace per quarter. This was substantially better revenue performance than it had ever achieved while rapidly growing prior to the pandemic.

Again, Uber chooses to withhold the data needed to better explain these huge pricing shifts but the biggest fare increases appear to be on the ridesharing, not the delivery side. Ample evidence has been reported in the press about massive increases in Uber taxi fares, including hard data from firms that process business expense charges. [5] In 2022 Uber increased its share of gross ridesharing payments by 32% (20.1% to 26.6%) while its share of gross delivery payments increased only 7%. [6] It is unlikely that Uber could have achieved comparable price increases in delivery markets which are much more competitive, and where Uber’s market position is much weaker.

The biggest recent change is that in the last year Uber significantly increased the share of each customer dollar that it retained, while the share retained by drivers (and restaurants) was comparably reduced. In the past year Uber increased its share from 18% to 28%. These are probably the most important numbers in the quarterly release and demonstrate an effective wealth transfer of $2.8 billion from labor to capital in just three months, which would produce an $11 billion impact if extrapolated to a full year.

Despite extremely tight labor markets, and the fact that drivers are fully aware that Uber customers are paying dramatically higher fares, and face huge pressures to cover skyrocketing fuel costs, Uber actually reduced the driver/restaurant share of total revenue per trip by 6% in the last year. Meanwhile the Uber shareholder portion of revenue per trip increased by 66%.

These big fare increases and the huge shift of revenue share from drivers to the company overwhelmingly explain how Uber has been able to substantially narrow its profitability problem. Other factors play a role (pandemic cost cutting, the rapid collapse of pandemic travel restrictions) but cannot explain the magnitude of recent financial shifts.

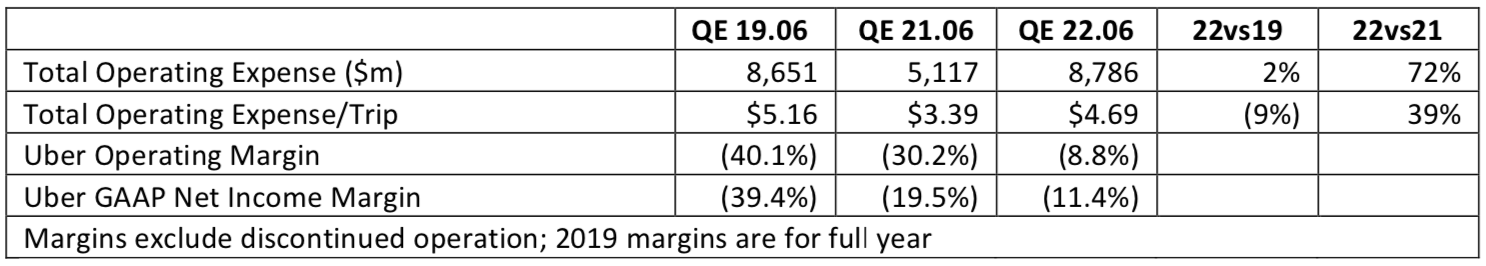

In 2019, when pre-pandemic demand was at its peak, Uber was producing negative 40% Net Income margins; Uber revenue per trip averaged $1.89, but Uber’s operating expenses per trip were $5.16. Two years into the pandemic the gap between revenue and operating expense per trip was $2.60 versus $3.39, as pandemic cost cutting and the initial stage of fare hikes could not keep pace with lost demand.

The very recent huge revenue increases were only partially offset by the cost of increased operations. Total Uber revenue increased 105% year-over year while operating expenses increased 72%. Uber revenue per trip increased 66% while operating expense per trip increased 39%. The gap between revenue and operating expense per trip has been narrowed to $4.39 versus $4.69 so Uber is still losing significant sums–$1.1 billion in the first half of 2022. Its second quarter operating margin was negative 8.8% and its net margin was negative 11.4%. [7]

Uber Has Completely Abandoned Its Original, Failed Corporate Strategy, and Has Reverted to a Lousier Version of What Traditional Taxis Had Been Doing for Years

Uber’s corporate development prior to the pandemic was entirely based on hyper-aggressive volume growth that sought to dominate and substantially expand global car service markets. It offered substantially more car service at much lower prices than traditional taxi operators had offered. Its approach was explicitly modelled on unicorns such as Amazon where a popular market entry provided the foundation for dynamic growth fueled by scale/network economies and synergies that facilitated rapid, profitable expansion into a wide range of similar businesses and markets. Uber’s financial strategy was entirely focused on achieving huge ongoing valuation growth, based on capital market perceptions that its rapid volume growth signaled the same type of economics that other highly publicized unicorns had demonstrated.

As this series has documented in detail, that strategy never had any hope of producing sustainable profits. Unlike other unicorns, it was actually less efficient than the traditional taxis it was driving out of business, its rapid growth and popularity was driven by billions in predatory subsidies that were always unsustainable, and it never had the significant scale/network economies needed to “grow into profitability.” The enthusiasm of capital markets reflected the power of artificial narratives Uber had manufactured, and the refusal of Wall Street and the business press to critically examine its various claims or its actual financial results.

Today, Uber is offering much worse service at much higher prices than the traditional taxi industry that it had “disrupted”. [8] Traditional taxis were unpopular because the only way they could keep fare revenues and costs aligned was to limit service to the densest, highest demand neighborhoods (maximizing revenue utilization and avoiding empty backhauls) and rationing service during big demand peaks. After entering the market Uber significantly increased service during peaks and to lower demand neighborhoods. It lost a fortune and has now retrenched to the much narrower service areas Yellow Cab had served. In its early years Uber aggressively promoted that its policy of not showing drivers trip destinations would prevent them from avoiding trips to neighborhoods that Yellow Cab drivers had avoided. Uber just announced that it has totally abandoned that policy, and drivers will have the full ability to refuse any rides that drivers think won’t be worthwhile, [9] Today, Uber offers the same poor service as traditional taxis, but must charge enormously higher fares because of its much higher cost structure.

Usually, companies that have achieved big financial gains are anxious to publicize how they achieved them and how they are likely to drive ongoing improvements, but in this context perhaps Uber has good reason to downplay, if not conceal the reasons for its recent progress. It is loathe to say anything that might acknowledge the complete dismal failure of its original, longstanding business model. It is probably even more reluctant to acknowledge that it is adopting much of Yellow Cab’s more efficient operating model. Using algorithmic manipulation and other more extreme forms of market power to transfer wealth from workers to shareholders is a widely used technique for boosting P&L results, but companies never want to say that out loud, especially in cases like Uber where it has become the overwhelmingly most important source of profit improvement.

After Many Years in the Financial Wilderness, Has Uber Actually Turned the Corner Towards Real Profitability?

While further, marginal P&L gains may be possible, the big fare and revenue share gains that drove the big gains in the last year do not appear sustainable. None of it was due to any new, more efficient practices, unless you consider the retrenchment back to the narrower Yellow Cab era service areas to be an efficiency enhancing innovation. Much higher fares and reduced service suggests limited potential for demand growth beyond the one-time rebound from depressed pandemic levels. Other similar industries (hotels, airlines, car rentals) have gotten the market to accept the combination of inferior service and much higher fares given the chaos created by much higher inflation and pandemic disruptions, but it is hard to believe that these recent market conditions are sustainable, or that customers would be happy paying steadily higher fares.

Given its ongoing losses, Uber had made numerous previous attempts to force drivers to accept smaller shares of customer payments. Given the market power created by its dominant share of the industry, many attempts succeeded in the short-term but after a point tended to collapse once driver frustrations reached a boiling point. [10}

The August 4threlease of Lyft’s second quarter 2022 results further complicates any attempt to understand Uber’s improved performance. There is very little meaningful difference between the two ridesharing services, and through 2021 there was no evidence of major differences in competitive or financial performance. [11]

But Lyft has experienced substantially less revenue growth in 2022 than Uber. Lyft achieved 30% greater revenue year-over-year in the second quarter while Uber achieved 105% revenue growth. Lyft revenue relative to volumes grew 12% while Uber grew 66%. This suggests that Lyft achieved only a small portion of the price increases that Uber was able to impose. Lyft does not report gross customer payments so it is impossible to tell whether they were able to capture a significantly higher share of those payments from drivers, as Uber had, but the lower rate of overall revenue growth suggests that they did not.

While Uber achieved major improvements in GAAP Net Income, with margins improving from negative 38% for full year 2021 to negative 7.4% for the first half of 2022 (after adjustments to only show results for ongoing operations), Lyft’s GAAP Net Income margin remained flat at negative 31%. Uber’s operating costs rose more slowly than the growth in revenue, but Lyft’s operating costs did not.

These comparisons underscore how important big fare increases and the big shift of payment share from drivers to the company was to Uber’s reported financial improvements, but it begs the question of how Uber would have been able to achieve pricing and driver share shifts this huge during the first half of 2022 while Lyft could not. Customers and drivers can shift between Uber and Lyft with relative ease. While their response to pricing and compensation changes might not be instantaneous, it is hard to believe those changes would not be readily noticed, and harder still to believe that they market would continue to passively accept fare and driver compensation differences this large. While the post-pandemic revenue rebound has been beneficial for everyone, Lyft results cast doubt on the idea that the underlying economics of ridesharing have fundamentally improved in ways that puts the industry on a path to robust, growing profitability.

The Real Issue Is Corporate Valuation, Not Quarterly Results

As this series has discussed at length, Uber and Lyft have remained largely immune to economic gravity because their hugely successful PR/propaganda campaigns created the widespread impression that it was a hugely innovative and powerful company, and that its robust top-line revenue growth meant that it had the potential to realize years of Amazon/Facebook type valuation growth.

There was always a robust market for the stock. Some people may have fully bought into the narrative claims suggesting years of profitability. Others many have been simply wagering that Uber’s broad market popularity would, like Tesla and other companies, ensure strong equity appreciation regardless of near-term P&L performance.

Uber’s IPO demonstrated the power of this dynamic. The new financial information disclosed in the IPO prospectus clearly laid out the horrible financial results and offered no coherent explanation (aside from vapid claims about becoming the “Amazon of Transportation”) as to how Uber might reverse these losses, much less produce the many years of rapid, highly profitable growth needed to justify the stratospheric valuation it was pursuing. Short sellers correctly wagered against Uber’s visions-of-sugarplums valuation objectives but no one in the market was challenging the broad market consensus that future robust, profitable growth justified a substantial 11-digit valuation.[12] $32 billion in GAAP losses through year 13 certainly demonstrates that its stock market valuation never had anything to do with evidence of future streams of profits.

In concept, recent events should have created even stronger valuation headwinds for Uber and Lyft, including the growing recognition that the market had massively overvalued “tech” companies who were focused on top-line revenue growth but not profits, the end of macroeconomic policies that had financed wanton speculation, huge fuel price spikes and the growing likelihood of recession.

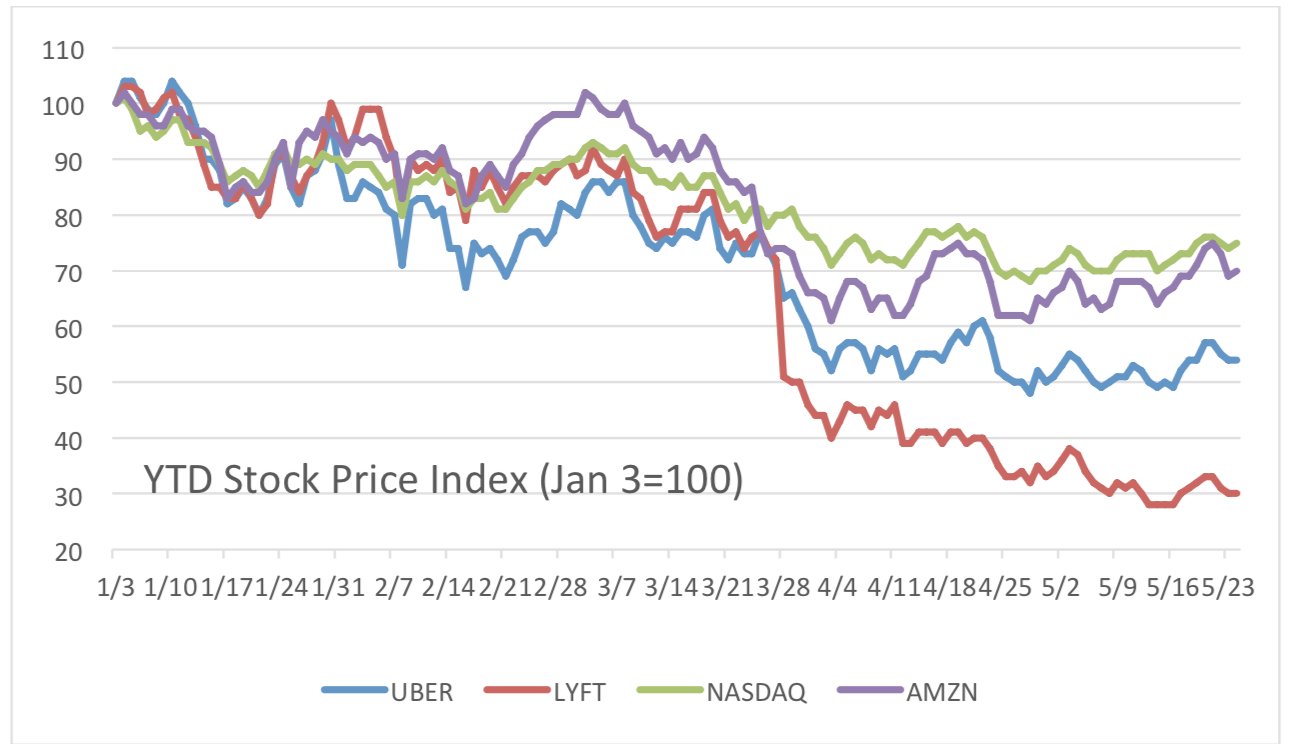

The stock price index table below shows price declines since the beginning of 2022 through the end of July for the Nasdaq composite index, Amazon, Uber and Lyft. Amazon and the Nasdaq index values have fallen 25-30%. But this demonstrates the impact of these broader recession/inflation/market correction factors on companies with proven business models that had produced strong profits for years. A wide range of companies (e.g. Crypto, Web3, Decentralized Finance) whose valuations were entirely narrative driven have been completely decimated.

These trends, and other evidence in recent months suggested that Uber and Lyft might suffer because of the market’s increasing focus on sustainable profits. [13] But the stock market’s immediate response to this week’s earning announcements is to assume that the bubble conditions of 2016 remain fully intact. Both stocks rose on the news that the post-pandemic recovery of top-line revenue exceeded analysts’ expectations, and that both companies achieved “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability.” The markets were not responding to structural changes Uber made to increase profitability, since Uber didn’t explain what changes it had made, and Uber’s public narrative remains wedded to pre-pandemic narrative claims about its unicorn-like economics and becoming the “Amazon of Transportation.”

Even if Uber continues to marginally improve profitability, logically this should have no impact on its valuation. A marginally profitable, slow-growth taxi company is not worth the $45 billion Uber was valued at on July 29thor the $62.5 billion it was valued at on August 4th. The conventional wisdom driving corporate valuations and market bubbles are incredibly resilient but can burst overnight. If these valuations significantly change it will likely have nothing to do with changed rideshare marketplace conditions or financial performance, but could easily result from broader, larger market corrections.

________

[1] Uber Part Twenty Nine (February 11, 2022) presented a more detailed version of this table showing financial results from 2014 through the end of 2021. That table, and the 2019 column of this table, also adjust published results to spread stock based compensation expense realized immediately after Uber’s 2019 IPO across a longer time period. In this case Uber was following proper accounting practices; it could not report these as current expenses until the day they actually vested, but this produced third quarter 2019 Uber P&L numbers wildly out of line with all other time periods.

[2} News media coverage has increasingly emphasized Uber’s GAAP Net Income results while downplaying, if not dismissing Uber’s efforts to focus on “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability.” For example, “Uber has long been criticized based on the way it calculates its adjusted profits. The company’s definition of EBITDA includes an unusually large list of exclusions and is widely seen as an inaccurate measure of the company’s overall profitability.” Andrew J. Hawkins, Uber’s seeing positive cash flow for the first time ever, The Verge, 2 Aug 2022

[3] For a graph contrasting the wild volatility of Uber’s “official” profit numbers, with the clear pattern produced by numbers corrected to only show results from ongoing operations, see Uber Part 24, February 16, 2021.

[4] Daniel Howley, Uber beats revenue expectations, stock soars despite $2.6B loss, Yahoo Finance, 2 Aug 2022, Jackie Davalos, Uber Soars After Beating Estimates as Ridership Defies Inflation, Bloomberg, 2 Aug 2022;

[5] Kate Conger, Prepare to Pay More for Uber and Lyft Rides, New York Times, May 30, 2021, Winnie Hu, Patrick McGeehan and Sean Piccoli, You Can’t Find a Cab. Uber Prices Are Soaring. Here’s Why, New York Times, June 15, 2021, Whizy Kim, Let’s Talk About The Real Reason Ubers Are So Expensive Now, Refinery29.com, July 7, 2021, Preetika Rana, Uber, Lyft Prices at Records Even as Drivers Return, Wall Street Journal, Aug. 7, 2021, Bobby Allyn, Lyft And Uber Prices Are High. Wait Times Are Long And Drivers Are Scarce, NPR, 7 August 2021, Laura Forman, At Uber and Lyft, Ride-Price Inflation Is Here to Stay, Wall Street Journal, 4 October 2021, Tom Dotan, Uber and Lyft prices are staying stubbornly high, despite drivers returning to the ride-hailing platforms, Business Insider November 11, 2011; Jeanette Settembre, Uber ‘taking advantage’ of unsafe NYC with astronomical fares, New York Post April 15, 2022; Henry Grabar, The Decade of Cheap Rides Is Over, Slate, May 18, 2022; Preetika Rana, Uber and Lyft’s New Road: Fewer Drivers, Thrifty Riders and Jittery Investors, Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2022; Tom Dotan and Nancy Luna, Leaked memo shows Uber raising prices for rides in one major US metro area to help drivers deal with high gas prices, Business Insider, Jun 16, 2022. Also see Uber Part 29 for an independent study of fare increases in Chicago based on the city’s new ridesharing database.

[6]Uber Technologies, Inc., Q2 2022 Earnings Supplemental Data, Aug 2,2022, p15-16.

[7] Consistent with the previous P&L table, all profitability and margin data has been corrected so they only reflect the results of ongoing operations, and in the case of 2019 have been adjusted to spread the cost of post-IPO stock awards over four years. Because of this anomaly the 2019 margins in the table reflect full year 2019 results, not second quarter (when the stock awards were issued).

[8] Asher Schechter, “Uber Has Higher Prices and Worse Service Than the Taxi Industry Had Ten Years Ago”, ProMarket, July 28, 2022

[9] Ashley Capoot, Uber unveils new features, including one that lets drivers choose the trips they want, CNBC, Jul 29, 2022

[10} A major 2016 Uber effort to cram down driver compensation was discussed in the very first post in this series (November 30, 2016) as was Uber’s need to retreat after it could no longer get enough drivers to meet customer demand (see Part Eleven, December 12, 2017). Once driver compensation has been pushed to minimum wage levels, and significant numbers of drivers are forced to sleep in their cars, there is little further potential to force them to accept smaller and smaller shares of customer payments.

[11] Part Twenty Nine provided a detailed comparison of results for the two companies through the end of 2021.

[12] The investment banks bidding for Uber’s IPO work initially promised a $120 billion valuation, the IPO was finally priced to achieve $90 billion but only achieved $65 billion. Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Nineteen: Uber’s IPO Prospectus Overstates Its 2018 Profit Improvement by $5 Billion, April 15, 2019; Can Uber Ever Deliver: Part Twenty: Will the “Train Wreck” Uber/Lyft IPOs Finally Change the Public Narrative About Ridesharing?, May 30, 2019

[13] Ryan Vlastelica, Uber Misses Out on Reopening Trade as Investors Crave Profitability, Bloomberg 1 Aug 2022