I’ve been writing a series of development economics posts, trying to highlight successes (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Dominican Republic, Poland, Turkey), failures (Pakistan, Haiti, Ukraine), and countries that are somewhere in between (Philippines, Jamaica). In general, I’ve been trying to think about these stories using the framework offered by the economist Ha-Joon Chang and the author Joe Studwell. Essentially, the idea is that A) it’s much better in the long run to be a manufacturing country than a natural resource country, and B) exports are really important for importing foreign technology and business practices. This theory — which is now getting a little bit of renewed attention from economists — is a refinement of the industrial policy ideas of Alexander Hamilton, Friedrich List, and various economists at the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

So far the general framework has held up pretty well. The successful countries haven’t followed the Chang/Studwell recommendations to a T. Nor have the industrialists been right in all their policy prescriptions — the examples of Poland and Indonesia, for example, suggest that foreign direct investment is a lot more useful than Chang thinks. But the new crop of successful countries have all exported a lot of manufactured goods — mostly to the U.S., Europe, and the developed countries of Asia. Doing that is easier said than done — no country can just magic export industries into existence — but the general family resemblance is encouraging.

There’s one major developing country, however, that bucks this emerging conventional wisdom in a big way. And it’s the country that people ask me to write about most often. So today’s post is about Mexico.

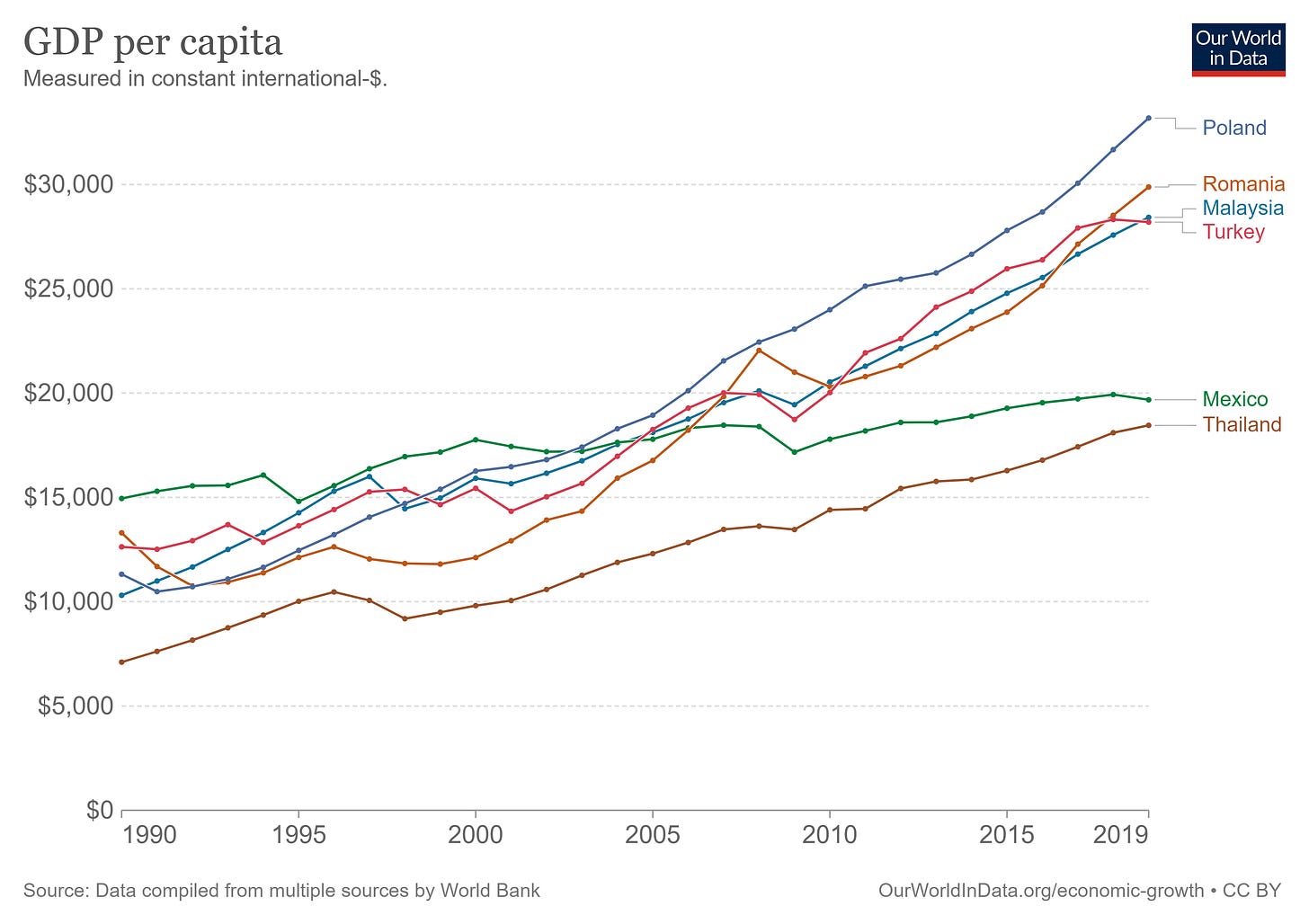

In 1990 — when catch-up growth started to become widespread — Mexico was a bit richer than Turkey, Poland, Romania, and Malaysia. But three decades later, Mexico had grown only modestly, while these others had surged past it and left it in the dust:

Even Thailand, which started out at only half Mexico’s income level, and which is widely regarded as the poster child for the dreaded “middle income trap”, has almost caught up with Mexico.

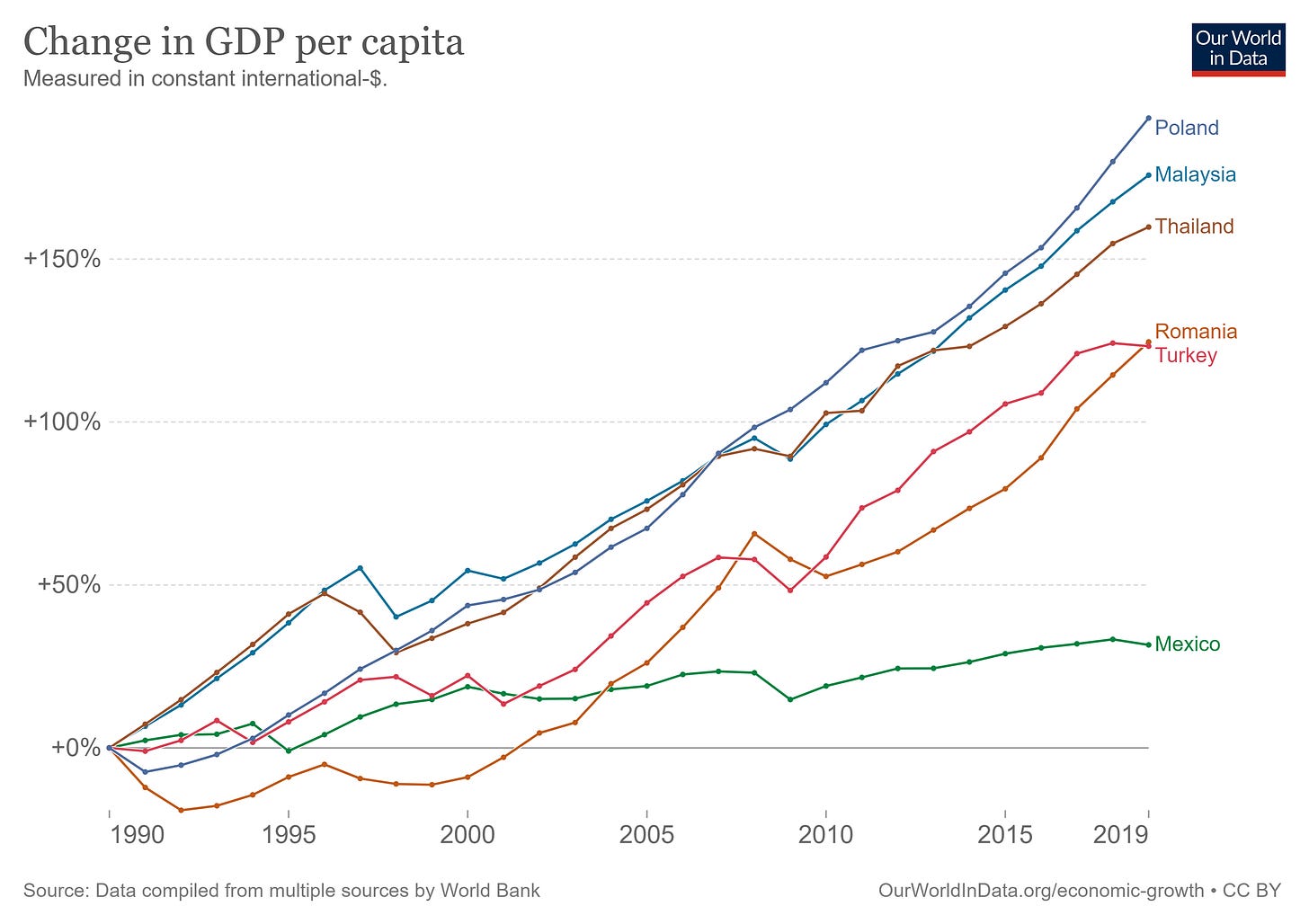

Mexico’s underperformance is even more striking when we look at growth in percentage terms. Mexico’s peers have more than doubled their incomes, while Mexico has grown by only about a third:

I don’t want to paint Mexico as a total failure or a basket case here. $20,000 (at PPP) is a respectable income, and puts Mexico above the global median. We’re not talking about a country like Pakistan, which has stalled at less than a third of Mexico’s income level. Mexico has had real achievements, like increasing literacy steadily to over 95% and reducing inequality substantially since the ‘90s.

But ultimately, everything flows from growth. Growth provides the resources to redistribute, and to spend on public services like education and health. And while $20,000 per person is not anything to sneer at, it’s not developed-country status either. Mexico needs to do better.

And worryingly, Mexico has suffered a growth stagnation even while enjoying a ton of natural advantages and using an economic model similar to that of the successful countries. What we’re looking at here is a big development mystery.

Slow growth from a relatively high starting point is a pretty common story in Latin America — Brazil, Colombia, and Argentina all have growth paths pretty similar to Mexico’s. But those South American countries have an excuse — they’re mainly natural resource exporters. Mexico’s top exports, on the other hand, are manufactured products, mostly electronics and vehicles:

This is a lot of exports, too — about 40% of GDP, similar to Romania and higher than Turkey. Overall, manufacturing is 18% of Mexico’s GDP, slightly higher than for Poland or Romania.

Mexico has another huge advantage that its South American counterparts lack: close proximity to a major economic center. More than 75% of Mexico’s exports go to the U.S., its behemoth neighbor to the north. Just as Poland, Romania, and Turkey benefit from their proximity to Europe, Mexico is part of a continent-sized economic agglomeration. The economic integration of Mexico with the U.S. is helped by the existence of a free trade agreement, the USMCA (formerly NAFTA).

As Poland does for Germany, Mexico makes a ton of cars and trucks for United States automakers — so much so that protectionists perennially lament the “giant sucking sound” that moves good union auto jobs to Mexico. And like Malaysia, Mexico exports a ton of electronics — in fact, it’s the world’s 8th-largest exporter of ICT goods, with a volume almost matching the U.S.’ total. In fact, the breadth of the products that Mexico makes is pretty spectacular. In terms of economic complexity — something that industrialists believe is a good predictor of growth — Mexico ranks 19th out of 133 countries in the OEC’s database, just behind China and ahead of Israel, Belgium, Denmark, Poland, Malaysia and the Netherlands.

In other words, Mexico is a technically sophisticated and highly diversified manufacturing nation that makes and exports large volumes of complex, high-value-added goods. That is almost always the description of a rich, industrialized country, or at least a fast-growing near-rich country like Malaysia or Poland. And yet Mexico is a middle-income country that’s growing more like a natural resource exporter.

It’s very hard to find any glaring problem with this story. Unlike Pakistan, Mexico invests a good amount — its gross capital formation is 20% of GDP, similar to Malaysia or Poland. It tends to run a trade deficit, but not a big one, and 2019-20 saw a surplus. Mexico has urbanized steadily, as most successful developing countries do, and most of its population now lives in the cities. It has a very high literacy rate, as mentioned above. It used to have frequent macroeconomic crises, but its inflation rate has been stable and low since the turn of the century. Government debt is low and fairly stable.

So Mexico has done a lot of things right, whether you believe the industrialists who emphasize manufacturing and exports, or the neoliberals who emphasize free trade and macroeconomic stability. Why hasn’t it grown more?

The most obvious hypothesis here is organized crime. Mexico’s drug cartels are among the world’s most powerful and deadly — the “drug war” between these groups is so intense that it is routinely classified alongside full-blown military conflicts like the wars in Syria and Yemen. It’s estimated that since 2006, about 350,000-400,000 people have been killed by homicide in Mexico, often in gruesome mass killings where bodies are left on display. Political officials are often murdered or forced to do the bidding of cartels. That undoubtedly creates a climate of fear that chills domestic investment.

And mafia doesn’t just terrorize the population; it also exacts a shadow tax on businesses. The Economist recently interviewed a Mexican businessman who talked about how common it is to have to pay protection money to the mob. This may be an even more severe instance of the phenomenon that makes the south of Italy so much poorer than the north — except instead of just one region of the country, it’s the whole country.

If a nation cannot maintain a near-monopoly on the use of force and enforce the rule of law, it cannot have a well-functioning economy.

But organized crime is not the only explanation for Mexico’s slow growth, which was well in place long before the “drug war” began in 2006. The economist Gordon Hanson has a 2010 paper discussing a number of possible factors. These include:

Let’s take a look at these factors.

Hanson’s first hypothesis is that Mexican banks are simply unwilling to lend to private companies. He notes that in the 2000s, Mexico’s private sector lending was pretty low, perhaps held back by the memory of a financial crisis in the 90s. But in the decade that followed Hanson’s paper, domestic credit to the private sector rose continuously as a percent of GDP, and yet growth itself did not accelerate.

Hanson’s second hypothesis is poor infrastructure, especially in energy and telecoms. Telecom prices fell in the years after Hanson’s paper, but it is true that Mexican electricity prices are still unusually expensive:

Expensive energy hurts competitiveness and generally gums up the whole economy, since just about everything requires some input of energy. So Mexico should probably invest a lot in improving its energy infrastructure.

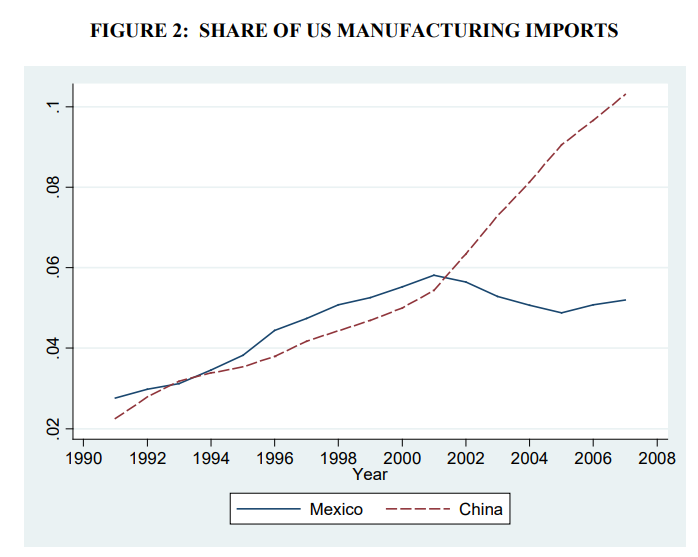

Hanson also mentions competition from China, noting that U.S. buyers increasingly turned to Chinese suppliers rather than Mexican ones in the 2000s:

But I’m pretty skeptical of this explanation, for a number of reasons. For one thing, many other developing countries grew very strongly in the 2000s and 2010s despite Chinese competition. Turkey, Poland, Vietnam, and Malaysia seemed to have little problem. And in the 2010s — after Hanson’s paper came out — higher Chinese costs have sent manufacturers looking for cheaper places to make their goods. Mexico hasn’t really won that competition, and its growth hasn’t accelerated. On top of all that, as we see from the export data above, Mexico is still a fairly export-oriented economy, despite Chinese competition.

The final Hanson hypotheses are 4) overregulation, and 5) informal businesses (which are impossible to tax and have difficulty growing in size). These two really go together, because if you over-regulate your businesses, they have an incentive to go off the books. The Economist agrees with this diagnosis:

Mexico ranked 60th of 190 countries in the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business index (which ceased publication after 2020). It can be a struggle to get electricity. Paying taxes takes a whopping 241 hours per year on average for firms in the formal sector…

Formal businesses face red tape and high taxes in exchange for poor public services. That is why so many firms and employees stay informal.

Over-regulation is always a plausible hypothesis for slow growth, but it’s maddeningly difficult to prove. There’s no one single measure of regulation, so everything is anecdata. The World Bank’s “ease of doing business” ranking is commonly cited, but the measure was abolished in 2020 after data irregularities and ethical issues came to light. The tax hours number is scary, but doesn’t seem to take into account the number of people Mexican companies assign to do their taxes (what if it’s just one guy working for six weeks?). Economists have tried to create “economic freedom” or business climate rankings that predict growth for U.S. states, and these efforts have generally been quite disappointing in empirical terms. So while I’m certainly willing to entertain the hypothesis that Mexico is simply regulating itself to death, I think it’s useful to look for other explanations as well.

A final factor that Hanson doesn’t mention is poor education. Mexico scores poorly relative to other OECD countries in international tests of reading, math and science. Low human capital can hold back a transition to higher-value-added industries. It’s not clear how much of this is cause vs. effect — Mexico is also poorer than other OECD countries, and if it did get richer, it might have better childhood nutrition, more money to spend on education, etc. But in any case, Mexico should definitely try to improve its education system (and bring in skilled immigrants from countries with good systems, of course).

So the upshot of this list is that there’s no obvious, glaring silver bullet when it comes to slow Mexican growth. The country needs to do all the usual pro-growth stuff — better energy infrastructure, better education, streamlined regulation. But it’s not clear that any of that will be decisive, especially since other factors like macroeconomic stability, credit provision, Chinese competition, and telecom costs have failed to really move the needle.

My own guess — and this is only a guess — is that reducing violence has the best chance of jump-starting Mexican growth. Countries at war always suffer economically, and Mexico’s violence is so intense that it’s often considered to be an actual war. A safe environment is simply a prerequisite for businesses to invest and grow. So if I were Mexican leaders, that would be my main focus.

In the meantime, Mexico’s case presents a puzzle and an anomaly for both of the common theories of development — the “industrialist” theory of Chang and Studwell that emphasizes high-value manufactured exports, and the “neoliberal” orthodoxy that emphasizes free trade and prudent macroeconomics. It’s just one country, but it’s an uncomfortable exception that should make development theorists question just how much they really know about why countries grow.