Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency investments are still being advertised aggressively all over the world. On my recent trip to Tokyo I saw glowing billboards with giant Bitcoin signs and bookstores with tables piled with books about NFTs. When I walk through downtown San Francisco, FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried’s face looms at me from every street corner, telling me: “THE FUTURE OF INVESTING IS CRYPTO. YOU IN?”

Most regular shlubbs who buy into crypto are probably not going to do a deep, careful analysis of its fundamental value, either as a currency or as a technology. Instead, they’re probably going to buy in because some guy at work bought Bitcoin back in 2013 and now he drives a Lamborghini, or their cousin turned a profit on some NFT. But the stories associated with Bitcoin and web3 probably do have some importance here. When regular shlubbs ask themselves “Wait, why am I buying this thing again?”, it helps to have a story to tell for why it’s a good investment, even if that story alone wouldn’t have convinced them to buy.

So I think it’s helpful to take a hard-nosed look at some of the economic stories that are floating around there in the crypto world. These stories are hard to pin down precisely, because — crypto being the decentralized enterprise that it is — there is no one authority that tells you what to think about Bitcoin or the Metaverse etc. So characterizing the stories that are floating around out there always puts one in danger of straw-manning. Nevertheless, I think there are some important economic errors in the stories I see people telling about crypto, on Twitter and elsewhere — errors that have important implications for how we should think about the value of Bitcoin and other blockchain assets.

Bitcoin boosters generally present Bitcoin as an alternative to fiat money like the U.S. dollar. They give lots of reasons why fiat currencies will always fail, and many love to declare the death of the dollar (always prematurely, so far). This forms the core of an investment thesis — if the world is going to switch from paying for things in fiat to paying for things in Bitcoin, then people who hoard lots of Bitcoin early on will end up being very rich if and when when the switch happens.

I think this investment thesis is pretty clearly wrong, and that Bitcoin will never actually become a currency. David Andolfatto has a good explanation of why. (Disclosure: I nevertheless do own some Bitcoin, for other reasons.) But the case for Bitcoin replacing fiat also has a moral dimension, which is subtler to rebut. Regardless of whether or not Bitcoin does replace the dollar, its proponents often argue that it should replace the dollar, because the dollar is inflationary.

“Inflationary” simply means that the dollar’s value — in terms of real useful commodities like bread, gasoline, and doctor’s appointments — goes down over time. The Fed targets a 2% inflation rate, and usually inflation stays fairly close to that numbers (though not right now). This is why a dollar is less valuable than it used to be — $1 dollar in 1913 was about as valuable as $30 in 2022.

To many Bitcoiners, this represents an injustice. Why should unaccountable, unelected bureaucrats in distant Washington, D.C. get to devalue your hard-earned cash? To these folks, Bitcoin seems to represent individual autonomy, because the Fed doesn’t get to decide how much your money is worth. And the idea that Bitcoin appreciates rather than depreciates over time seems to value personal frugality and probity, because it promises that people who work hard and save money will be able to keep the fruits of their labors.

But this idea rests on a fundamental misconception: The idea that cash should rise in value over time. In fact, cash was never meant to be a form of long-term savings.

Consider a world where cash goes up in value over time — where simply because you stuffed some money under a mattress, you can afford more and more of society’s production every year. This sounds like a pretty good deal, right? In fact, it is a good deal — too good, really. In this sort of deflationary world, you’re getting wealth for nothing — society is continually transferring you more and more of the fruits of its labors in exchange for you doing absolutely bupkis.

If money earns a positive real return over time, that return doesn’t represent a reward for hard work done; it represents a freebie. A handout. In economic terms, this is called “rent”.

If Bitcoin actually did become the currency of the land, and its value rose year after year, that rising value would represent a transfer of real resources to people who sit on cash and do nothing at all with it. And where do those real resources come from? Well, they must come from productive workers and companies. So the world Bitcoiners imagine is a world where productive workers and companies are subsidizing the lifestyles of cash hoarders.

That doesn’t sound fair. And it’s not economically efficient either. Economists argue back and forth over whether the optimal rate of inflation is 0 or some small positive number, but you will find very few who argue that the optimal rate of inflation is negative.

So if cash shouldn’t make you wealthier over time, what should? The answer is simple: Productive assets. When you invest your savings in a company, you’re (at least theoretically) funding that company to do something productive. By allocating your capital to productive projects, you’re not being a useless rentier, you’re being a capitalist — you’re taking on risk, and getting paid a return for taking on that risk.

That’s the source of one of the most fundamental principles of financial economics: the risk-return tradeoff. In a well-functioning financial market, earning a return is compensation for taking on risk.

That’s why a deflationary currency doesn’t really make sense. Something that’s a good short-term store of value (i.e., has low volatility) won’t be a good long-term store of value — i.e., it will not earn a high return. Good currencies are ones whose value is very predictable in the short term — thus, they are things that don’t earn good returns in the long term. (This is why Bitcoin, at least in its current form, will not be used as currency.)

In other words, cash should not be your primary savings vehicle. Your primary savings vehicle should be long-term productive assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate. You should hold only enough cash to make your monthly purchases, plus a small emergency fund. Your cash is your liquidity.

Now, there’s one big problem with this idea. Poor people aren’t easily able to hold productive assets, for several reasons. First, some productive assets like houses are simply beyond their reach. Second, they have low information and have trouble accessing financial markets where they can buy things like stock. And third, poor people have so little wealth that merely maintaining a small emergency fund will take up most of their entire savings. Thus, poor people are forced to hold their savings in cash.

This is a big problem, but the solution is not to switch our society to a deflationary currency so that cash earns a positive real return over time. Doing this would allow poor people to earn a tiny return on their tiny holdings of cash, sure. But most of the returns in this sort of regime would flow to people who are able to hold a ton of cash — in other words, to the rich. Giving poor people a few bucks of returns is not worth giving rich people a huge windfall of unearned returns. Instead, if you want to give poor people money to compensate for the fact that they can’t buy stocks, just give them cash benefits. Or buy stocks for them with a social wealth fund. Bitcoin is not the solution to poverty.

Much of the crypto world is based on the idea that the way to make something valuable is to make it scarce. This is one of the basic theses of Bitcoin — the idea that because the total number of Bitcoins will ultimately be algorithmically limited, Bitcoin will rise in value over time. It’s also the fundamental concept behind NFTs — if you take an easily copy-able jpeg of a monkey and you tell the world that only one person really owns that jpeg, people will pay for that exclusive feeling of ownership because it is scarce.

And finally, it’s one of the fundamental ways that people are trying to commercialize the Metaverse. Many people seem to have the idea that the next iteration of the internet will involve exclusive access to digital environments, like land but in the digital realm. Real estate represents a huge percent of the wealth in the physical world, so why not in the digital world as well?

Unfortunately this idea isn’t working out very well so far:

It could be that it’s just too early, and that eventually digital land will be a very big deal. But in fact there’s a deep reason to be skeptical that this idea will ever come to fruition: Scarcity, by itself, does not actually create value.

Some sloppy high school economics teachers might tell you that scarcity creates value, as a way of debunking the old utility theory of value. But in fact what creates demand is a combination of usefulness and scarcity — it’s how scarce something is relative to how useful it is, on the margin.

That’s just a wordy way of saying “Value is determined by supply and demand”. Simply restricting the supply of something doesn’t automatically make it valuable, because demand might be zero — this is why while some kids’ drawings become famous expensive NFTs, your own kid’s drawings are highly unlikely to command any positive price in the market.

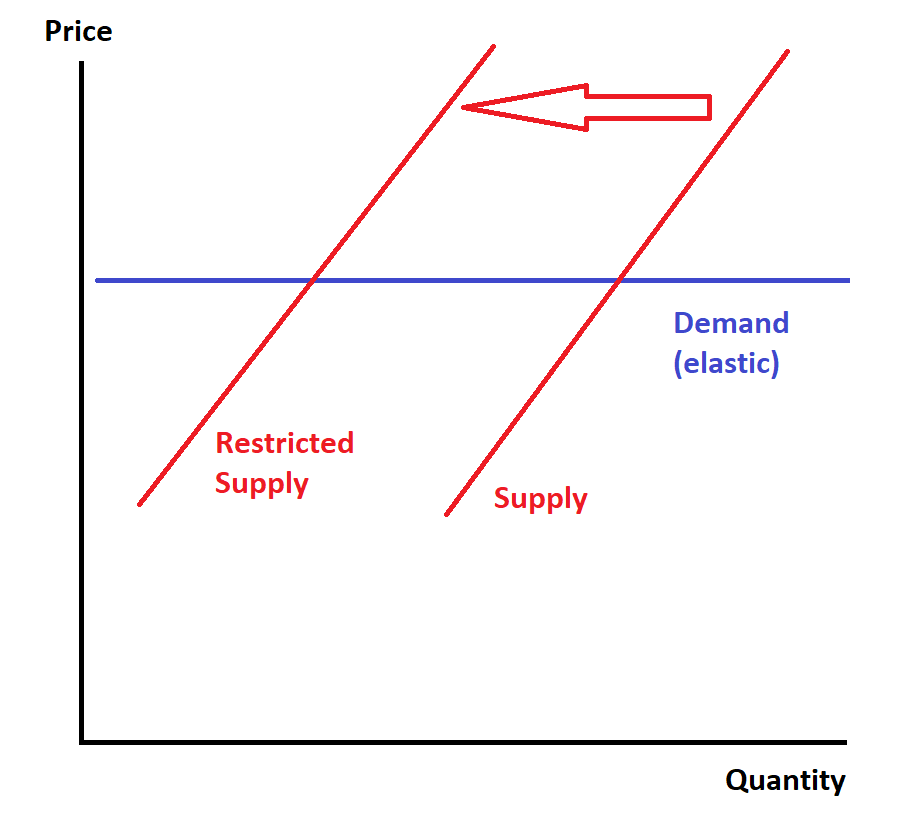

But even if there’s plenty of demand, artificially limiting supply might not pump up the price much at all. The reason is that the effects of supply shifts depends on the elasticity of demand. Let’s draw a picture.

In this picture, demand is perfectly elastic — people know what price they’re going to pay for something, and not one cent more. In this case, even though the thing you’re selling does have value — maybe lots of value! — restricting supply doesn’t raise the price at all. Instead, you’re just selling less stuff and making less money.

Now, this is a pretty simple model with no actual pricing power in the economy. I was just using it to make a point. More realistically, what if companies have market power, so that they have some ability to choose how much to sell and how much to charge for it?

In that kind of a world, companies can (and do) make their products artificially scarce in order to jack up the price. But this is a bad outcome — it’s a kind of market failure, because it results in the economy producing too little stuff. This is why economists don’t like monopolies.

So now apply this principle to the Metaverse. The amazing, awesome thing about the internet is that there’s room for everyone — it costs very little to create more “space” in digital environments, so people aren’t limited in what they can build, the way they are limited in the physical world. Putting artificial limits on how much people can access digital environments is raising price higher than marginal cost.

That’s either economically stupid or economically inefficient. In the case where the internet is competitive — where anyone can come in and create digital land for almost zero cost — then making your own digital land artificially scarce will just result in everyone walking away, as happened with the Metaverse products in the tweet above. In the case where you have some monopoly over some sort of digital land — for example, if you have a big existing social network that everyone already uses — you might be able to make a profit by limiting access and jacking up price. But this means you’re making the economy inefficient, by charging money for something that, based on its fundamental cost structure, ought to be free or nearly free.

Now there are a few exceptions to this general rule — things that people value because they’ve decided to use them as status symbols in a zero-sum status-signaling competition. We call these Veblen goods, and they do exist (authentic Rolex watches being a good example). If you can make your NFT or your Metaverse property into something people decide to splurge on just to prove how rich they are, more power to you, I suppose.

In general, though, scarcity doesn’t create value. Limiting your own product until it’s as rare as diamonds will not make it as valuable as diamonds. In fact, often it will just lose you money.

Crypto people think a lot about economics, and that’s good. But too often they think about it in loose, impressionistic ways, or they engage in wishful thinking based on their own morals, or they simply misunderstand how basic econ principles work. And too often, they think they can force these misunderstandings to be true by yelling them at people over and over. Folks, it does not work like that.