Executive Summary

In the not-so-distant past, the typical career path toward becoming a financial advisor was to build up a book of business on one’s own, often by either tapping into one’s own personal networks or cold-calling prospective clients in bulk to generate enough business to gain a foothold. But the obvious flaw with this ‘eat-what-you-kill’ model was that newer advisors overwhelmingly succeeded or failed – not by virtue of the quality of advice they gave to their clients, but by how effectively they could sell the financial products for which they were usually compensated via commission.

In more recent years, however, the rise of the fiduciary advice model (in which the quality of advice provided to the client really does matter to the firm’s success) has allowed a new career path to emerge: that of the associate advisor, who generally takes on financial planning tasks, like data gathering and analysis, to support the lead advisor so that they can focus more on managing the client relationship and bringing in new business. And as the associate gains experience and trust among existing clients, they can gradually take over some of the lead roles themselves, to be supported by new associate advisors of their own – thus allowing the firm to transition its clients from the founder to the next generation of advisors.

But for many experienced advisors (and particularly those whose careers evolved through the older eat-what-you-kill model), integrating an associate advisor into an existing practice can come with its own challenges. For example, seeing eye-to-eye on the expected responsibilities of the associate advisor’s role, as well as the role’s future possibilities and its meaning to the associate advisor’s career trajectory, may not come naturally, especially when the senior and associate advisor are each from distinctly different generations – which can result in dissatisfaction from both parties if they aren’t both clear and in agreement on the role’s purpose and where it is headed.

In this guest post, Penny Phillips, president and co-founder of Journey Strategic Wealth, uses her expertise in helping advisors address some of the common challenges in introducing new associate advisors into their firms and how senior advisors can scale their time and productivity to successfully integrate associate advisors into their advisory practices.

One of the most important components of bringing on an associate advisor is being clear about the purpose and requirements of the role during the hiring phase. And because associate advisors are often hired in the early stages of their careers, it should also be clear how they will be taught and supported by the firm to succeed in the role. This can be achieved by establishing a framework of Objectives central to the associate advisor role, as well as clearly identifiable Key Results that will help team members recognize whether they are achieving the desired results.

Furthermore, this Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) framework can also be extended to the associate advisor’s career development to define and work toward key skills that bring them closer to what they want to achieve. And as the senior advisor’s own role evolves with the addition of an associate, they may want to develop their own set of OKRs to ensure they are progressing towards their goals for themselves and their practice!

Ultimately, the key point is that finding and developing an associate advisor will take time and effort – for both the senior advisor and the associate advisor. However, a successful partnership between senior and associate advisors has the potential to last many years and can allow the practice to scale up in ways that aren’t possible for a solo advisor. Taking care to start the process on the right foot can therefore pay dividends for both parties in the long term!

Many financial advisors starting out as solo practitioners who strive to manage sustainable growth and scale their practices will eventually approach the ‘capacity crossroads’ where there are more clients than they alone can handle. At this point, these advisors will need to consider whether to stop adding more clients, or instead begin hiring one or more associate advisors to help them manage the ongoing growth of client relationships as their practice expands into a boutique. The associate advisors hired into these roles are critical to the continued scaling up of client headcount of the firm for 2 primary reasons: 1) they help create capacity for the primary advisor to continue their role as rainmaker to generate new business, and 2) they allow for the inevitable transition of client relationships away from the primary advisor as the client base grows further.

Unfortunately, the integration of associate advisors, particularly ‘next-gen’ advisors expected to take over client relationship management and perhaps someday even to take on business development and leadership responsibilities of the firm as well, has proven to be a challenging process for advisors.

For many large firms, the challenge of retaining financial advisors is rooted in our industry’s tendency to favor rainmaker-producers who excel in sales over advisor-planners who provide advice and manage relationships. This reliance on advisors as salespeople over advice providers has skewed the perception of what constitutes a successful financial advisor, associate or otherwise.

The larger problem we currently have in our industry is that there is an overabundance of aging solopreneur advisors who are not only the primary rainmakers in their practices but also the primary advisors and business operators as well. Many are completely at capacity while being faced with one of the most challenging tasks of all: finding other advisors to help them service and retain their current clients so they can continue to generate new relationships for their firms.

For these reasons, senior advisors can benefit from integrating next-gen associate advisors who are coachable, credentialed (ideally out of school), and who have strong relationship management skills so that they can focus on preserving the firm’s existing client relationships – and protecting its existing revenue sources – creating capacity for the senior advisors to focus more time and energy on generating new revenue. Despite the many reasons behind this challenge, frameworks exist that can help advisors successfully position, train, and develop reliable next-gen associate advisors to support the continued growth of the business.

Next-Generation Advisors Are Well-Suited To Non-Producer Advisory Roles That Solve For Capacity And Succession

The fact of the matter is that we live in a very different world today than the one that existed 30 years ago. And finding a next-gen associate advisor who is naturally adept at rainmaking and comfortable working solo is not a realistic expectation. There are several reasons for this.

The first is that many ‘next-generation advisors’ (i.e., advisors in their 20s and early 30s) grew up in a culture and era characterized by technology and social media. And because many of the tech-enabled tools and platforms at their fingertips were often designed to be used across teams, these Millennials often excel in team-based settings and tend to prefer collaborating with others over working solo. That is vastly different from the ‘lone-ranger’ culture in which many senior advisors started and built their careers.

Additionally, social media has dominated much of the younger generation’s everyday lives. We interact mostly virtually with everyone and everything, using social media to build relationships and rapport and even to build our own confidence and esteem. Our decisions about things we buy, places we visit, and services we engage with are also influenced by social media. Think about how this alone has impacted the traditional sales culture.

How The Right Expectations Of Next-Gen Associate Advisors Can Help Them Provide The Most Value To Their Firms

As mentioned earlier, because of the industry’s unhealthy overreliance on ‘producers’, many financial advisors have hired associate advisors with unrealistic expectations. I have coached hundreds of advisors over the past decade, and there are several things that I have heard repeatedly regarding the hiring of a new associate advisor:

- They expect the associate advisor to be comfortable networking and prospecting for new business;

- They expect the associate advisor to be able to uncover opportunities in their book of business immediately; and

- They expect that the associate advisor will be able to figure things out on their own and hit the ground running (e.g., navigating discovery conversations, introducing unique solutions to clients, etc.)

I don’t blame advisors for having these expectations. After all, they have been through the experience of having to figure it out on their own. And they were successful at it.

But the reality is that’s why those founder-advisors are founders and not employees in someone else’s advisory firm. Next-gen advisors with those skillsets don’t tend to take employee jobs; they tend to start their own firms. In addition, because most next-gen associate advisors actually have different skill sets, it’s important to clarify how they can provide the most value and what they can be expected to do within the firm.

For most new advisors in the early stages of their career track, this means serving as second chair in meetings, taking notes, handling prep and follow-up, handling service requests, and helping with data input and organization. By honing their skills through these responsibilities, new associate advisors not only learn the ethos of the firm but also create the capacity for the primary or senior advisors to focus on developing the business.

As associate advisors develop their skills and learn the firm’s culture, their responsibilities can grow to include managing the firm’s existing client relationships and helping maintain its revenue sources. In this capacity, their responsibilities could include managing lower-tier households by delivering advice, facilitating review meetings, and serving as the first point of contact for larger relationships.

Ideally, associate advisors would either already have met the education requirement for CFP certification or already have some experience as an advisor. To the latter point, firms who are searching to fill associate advisor roles may find that advisors struggling in a producer-oriented role at other firms may be good candidates, as while many who have failed at quickly building a book would still add substantial value to a team by servicing existing clients instead.

It’s also possible that good candidates are already on the firm’s team but in other roles; paraplanners or client service associates who may wish to move into an advisor track can also be considered potential associate advisors.

Managing The Associate Advisor’s Career Trajectory

Once an associate advisor has proven their ability to support lead advisors and care for clients and service them in a way that is aligned with the firm’s culture, the associate can generally take 1 of 2 career paths. Either they can take the leadership succession path of becoming the next lead advisor responsible for managing complex relationships and bringing in new business, or they can continue down the career path of what can be referred to as an ‘in-house’ or ‘service’ advisor primarily responsible for delivering advice to clients and managing the bulk of households in a firm. These advisors will always be mainly responsible for managing relationships and preserving revenue; they may or may not become future growers (and owners) of the business.

Some associate advisors will have natural business development skills; they may have a knack for finding opportunities while networking or will immediately enjoy meeting new people and talking about the firm. These are the advisors who should be quickly encouraged down the path of being a lead advisor. Other associate advisors may start to develop business development skills over time as they become more comfortable in their roles. The first 3 years of an associate advisor’s tenure in an organization are crucial in helping to inform what their long-term role will be.

Notably, some associate advisors, especially those who are young Gen-Y or even Gen-Z, may be naturally adept at business development, but in a way that is different from what senior advisors may be used to. Creating content, building a social media presence, leveraging platforms like YouTube, and developing as an influencer within a certain target group are business development tactics that should be encouraged for associate advisors who have the desire and ability to engage in them.

What Makes Next-Gen Advisors Thrive At Work

So how does this relate back to integrating new next-gen associate advisors into a firm? Well, it informs several things about how they will survive and thrive in an organization. Because of the instant-gratification and instant-feedback environments that younger generations have grown accustomed to, we know that it’s necessary to provide constant, real-time feedback – and positive reinforcement – to them.

It’s important to note that many senior advisors with decades of experience in this business started their careers in a negative reinforcement culture characterized by ‘sink-or-swim’ training programs. This may seem like a small nuance, but the way managers deliver feedback and guidance can greatly impact next-gen-employee retention rates.

Further, we know that collaboration and teamwork are key; next-gen associates need to learn from others on the team, especially those with experience in roles like their own. This can be accomplished through various methods: shadowing, mentoring, having ‘battle buddies’ (i.e., accountability partners that encourage and help each other to stick to goals), etc.

Providing constructive feedback to newer associate advisors is also important. One way to do this might be to allow the associate to roleplay presenting a financial plan, then to debrief by first identifying how they met or exceeded expectations and then reviewing areas for potential growth.

Lastly, we know that younger associates need to feel like they are doing purposeful work on a team that shares their values. It will be virtually impossible to retain a next-gen advisor unless they feel they are 1) involved in purposeful work, and 2) part of a firm culture they connect with. This is a crucial point that often gets overlooked. Advisors must ensure that their firm’s value proposition, mission, vision, and firm culture are easily explainable to new employees and felt throughout the organization.

How To Integrate Next-Generation Associate Advisors

Before hiring an associate advisor, a good practice for advisors to follow is to ensure the job description is optimized to help the advisor hit the ground running when they start. That can mean pulling the original job description and redesigning it so that instead of focusing on individual tasks the associate advisor will be (or is already) responsible for, it emphasizes what the associate advisor will be expected to achieve through a framework that focuses on reaching objectives, and how they will know they are achieving those objectives by recognizing clearly identifiable key results.

Frame Associate Advisor Roles Around Objectives And Key Results (Role OKRs)

The benefit of establishing Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) is that they serve as an accountability tool, keeping team members accountable for the types of activities that drive results. They also serve as a benchmark for whether team members are succeeding in their roles on an ongoing basis.

When introducing and reviewing OKRs, advisors can suggest behaviors and activities that will assist the associate advisor in meeting their OKRs, providing each associate advisor with a complete framework for what they are aiming to achieve in their role. Over time, as the associate advisor develops and requires less guidance, OKRs will be very helpful in helping them identify how and where to spend their time.

Some examples of an associate advisor’s ‘Role OKRs’ may look something like this:

- Objective: Build rapport with current clients.

Key Result 1: The associate advisor is always aware of critical information about a client before meeting or speaking with them, including any special preferences the client has.

Key Result 2: The associate advisor stays present with clients by communicating with them on an ongoing basis (e.g., providing topical thought leadership content or choosing clients randomly for weekly check-ins.)

Key Result 3: The majority of lower-tier clients reach out directly to the associate advisor rather than the senior advisor.

Behavior/Activity Suggestions: Associate advisors can proactively reach out to both top-tier and lower-tier clients on a regular basis to check in and provide relevant insight (e.g., providing updated performance reports, sending periodic check-in emails) and stay in touch with clients anytime there is a critical market event by providing relevant content on the event.

In order to help them accomplish this, senior advisors are encouraged to copy associate advisors on all correspondence, looping them into questions and requests from the client, and refrain from responding as much as possible, giving the associate advisor the opportunity to be viewed as the clients’ problem solver.

Additionally, associate advisors should conduct brief research on all clients prior to meeting or speaking with them. This can include a review of CRM notes and social profiles to ensure they are armed with information that can help them build rapport.

- Objective: Increase capacity for the senior advisor(s) in the organization.

Key Result 1: The senior advisor no longer prepares for or manages follow-up tasks from client meetings.

Key Result 2: The associate advisor prepares the senior advisor for client meetings at least 2 days in advance.

Key Result 3: Senior advisors add more households to the firm in the current year relative to last year.

Behavior/Activity Suggestions: The associate advisor completes follow-up tasks from the meetings of that week, taking on the bulk of the responsibilities of updating client plans and downloading critical information (e.g., performance reports). Additionally, they can proactively close the loop on any service items, questions, or concerns from clients that may still be outstanding from that week. They can also review the CRM to provide key points for the senior advisor to cover in client meetings, helping them easily identify previous follow-up items and what needs to be reviewed and discussed during the meeting.

In order to accomplish this, the associate and senior advisor can schedule meetings at the end of every week to review the previous week and plan for the upcoming week, and to ensure they are both clear on firm goals, including the number, type, and segment of households the team is seeking to add each year. By being intentional and holding each other accountable to exactly what constitutes success, senior and associate advisors can ensure they are always on the same page, helping them quickly identify when things are not working.

- Objective: Provide exceptional service to firm clients and deliver on the firm’s value proposition.

Key Result 1: The associate advisor will respond to all client emails within an hour and to all client phone calls by the end of the day, even if they don’t yet have an answer for them.

Key Result 2: The associate advisor will provide clients with a summarized follow-up to all conversations and meetings within 24 hours.

Key Result 3: The associate advisor will ensure that all clients with unresolved questions receive an update on the status of those items before the close of business each Friday afternoon.

Behavior/Activity Suggestions: Associate advisors can collaborate with the team to establish systems and processes to ensure they provide consistent service. This could include creating CRM workflows to systematize processes (such as onboarding a new client) and reviewing and revising these workflows at least annually.

The associate advisor can also create templates for themselves to assist in quickly sending follow-up reviews and other types of client correspondence sent repeatedly. Associates can also start and end each week by reviewing their calendars and email inboxes to ensure that all follow-ups and touch points needed that week were completed.

Importantly, the entire team must be clear on how the practice defines “exceptional service” and can revisit this each time a new associate or team member is brought into the organization.

Set Realistic Onboarding Plans

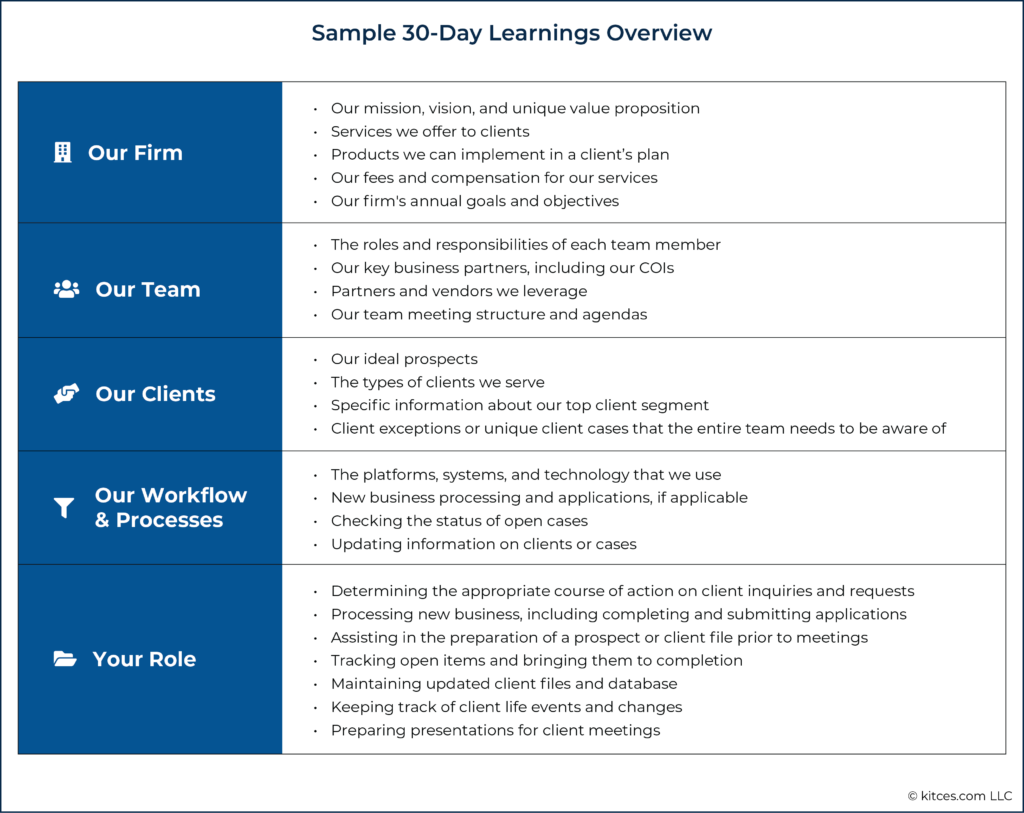

After ensuring that there is a mutual understanding of the expectations of the associate advisor role, senior advisors (or staff overseeing the hiring process) should provide a formal onboarding plan to the new employee.

The onboarding plan should incorporate several components, including:

- An overview of what the new employee is expected to learn within the first 30 days.

- A list of ways that the new employee can learn these things includes reading pitch decks, commentaries, and marketing material; having conversations with team members and key stakeholders; sitting in on meetings; listening in on client or prospect conversations (with permission); watching training webinars; etc.

- A weekly schedule for the first 4 weeks that includes time for tech tool demonstrations and, at the end of each week, scheduled meetings with the senior advisor to review key learnings and answer questions the associate may have. By the second week, associate advisors should begin sitting in on client meetings and listening in on conversations.

By providing employees with a framework for training and onboarding, firms can ensure that new team members have the tools and support to hold themselves accountable, stay on pace, and develop in a way that is natural to them.

Support The Development Of New Associate Advisors

Associate advisor development takes time, but should begin immediately within the first few months of joining the firm. A common question that senior advisors ask is, “How long will it take for me to be able to pass on relationships to an associate advisor?” The best response to this question was provided by Philip Palaveev on a Kitces Office Hours covering the same topic: “It takes as long as it takes.”

Creating Metrics That Help Assess Associate Advisor Development

Rather than focus on the amount of time it will take for an associate advisor to develop and grow (whether it be months or years), leaders should focus on the metrics or ‘mile markers’ that will indicate, over time, that the associate advisor is developing appropriately.

That list may look something like this:

- Ability to solve problems independently of the senior advisor, especially as it relates to questions about a client’s plan or accounts.

- Ability to powerfully leverage partners, including custodians and tech partners, to serve clients.

- Ability to summarize meetings and conversations and identify to-dos with limited input from the senior advisor.

- Ability to prep for meetings, including providing advisors with the necessary documents, notes, and reports from clients’ digital files.

- Ability to speak the same ‘language’ as the senior advisor, describing the firm’s value proposition and services in a uniform way.

Once the associate advisor has mastered the above, the senior advisor can review progress with the associate advisor to co-create other metrics that will help to indicate when the associate will be ready for an elevated role. These metrics should be tied to the associate advisor’s active listening skills, competency in financial planning, and ability to formulate plans and recommendations based on client data.

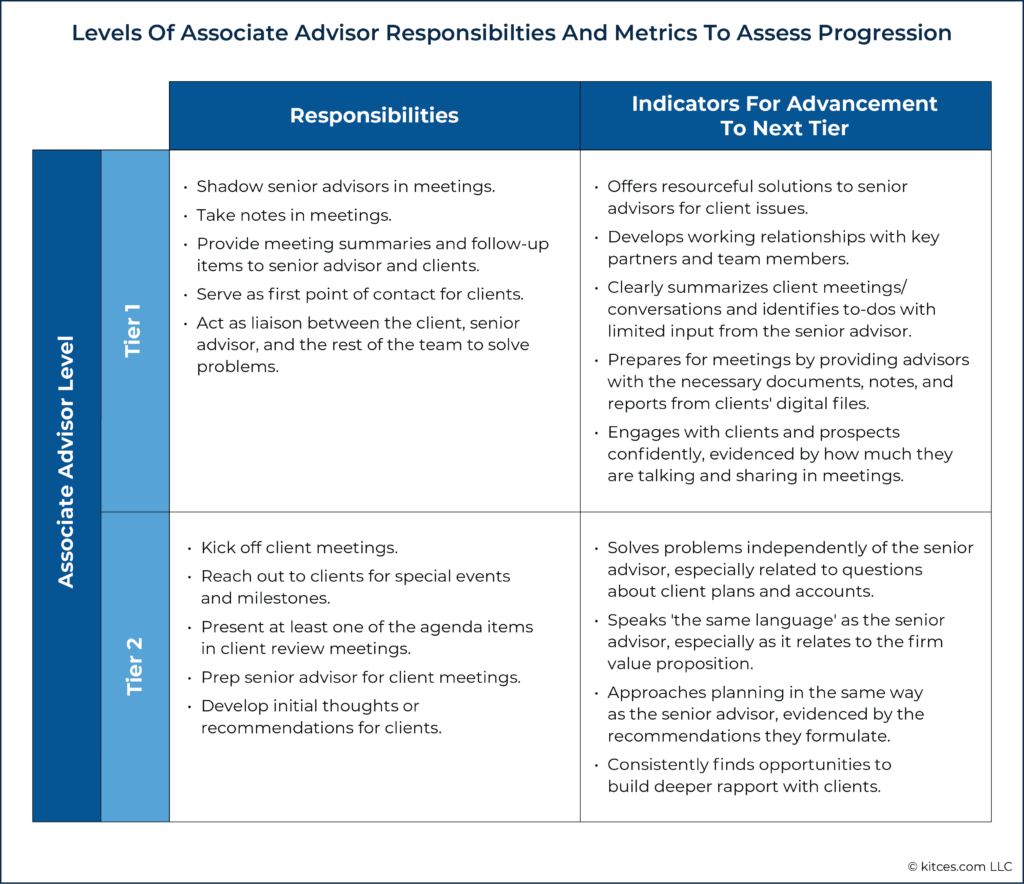

Some firms separate the associate advisor role into separate tiers (e.g., tier 1 and tier 2) prior to promoting them to a full advisor role so that the associate advisor can focus on learning about the business of their new firm and the technical elements of what they are required to do (e.g., responsibilities associated with Tier 1 Associates) before they move on to master the more nuanced responsibilities of effective communication and more comprehensive planning skills (e.g., responsibilities for Tier 2 Associates).

Helping Associate Advisors Meet Their Learning Objectives

In order to meet their ‘mile marker’ metrics, associate advisors need to spend as much time as possible watching, listening, and learning from other advisors in the organization. To support them, senior advisors should debrief with associates after as many meetings as they can.

Debriefing With Associate Advisors

Regardless of the role the associate advisor plays in client meetings, any time they are asked to present, speak, or display skills, the senior advisor can provide valuable support by immediately following up with a discussion to debrief how the encounter went. There are many ways that this may be done. One would be to immediately debrief for 20–30 minutes after each client meeting. The agenda could look something like this:

- Begin by reminding the associate advisor of the objective of the meeting or conversation they were just a part of.

- Ask for the associate’s feedback on the meeting. What did they learn about the client? What did they learn about the process? What phrases resonated most with them? What do they think they could have added to the meeting?

- Provide the associate with feedback on the meeting, pointing out things for the associate to reflect on, perhaps including a specific question asked by the client or a certain part of the conversation that was powerful.

- Review to-dos and action items from the meeting and allow the associate to share their approach to handling them.

- Provide feedback and direction on the associate’s approach.

For advisors with a high-activity practice where several meetings a day might take place, it may make more sense to hold one longer meeting with the associate advisor at the end of every week, for 90 minutes or so, where they can reflect on all the meetings of the week, reviewing the same set of points outlined above. (Tactical to-dos from each meeting can still be handled immediately after the meeting concludes.) This might be a better approach for people who need time to digest and reflect before jumping into a thoughtful discussion.

Regardless of which approach is taken, holding these debrief sessions consistently is crucial to the associate’s development. Asking open-ended questions that leave space for the associate advisor to reflect will also provide an opportunity for the senior advisor to evaluate critical thinking and active listening skills.

Here are several go-to questions to leverage with associate advisors:

- What did you notice about the client’s body language?

- What did you learn about the client’s relationship with money from that conversation?

- Which discovery question evoked the greatest response from the client?

- What were the client’s goals? How would you prioritize them?

- What do you think our next step should be?

- What did you learn about the client’s relationship with their family?

- What did the client share that will inform the way we think about crafting their plan?

Reviewing Client Data And Acclimating Participation In Client Meetings

Another powerful exercise to conduct with associate advisors on a weekly basis is to encourage them to review the discovery data for a top client (or a new client). Then, ask them to review the financial plan and draw correlations between the data they just reviewed and the services and products that the plan is recommending for implementation.

This is critical not only because it helps to train the associate, but also because it serves to institutionalize the way the firm does business. In other words, no matter who is servicing or serving the client, the approach taken is (almost) always the same.

Over time, as clients get used to engaging with the associate and have either provided positive feedback or shown they have built some level of trust and rapport with them, associate advisors can take a greater role in the relationship. Examples of this might include:

- Allowing the associate to begin the meeting ‘warm-up’;

- Teeing the associate up to present one of the agenda items in the client review, such as an update on portfolio performance;

- Encouraging the associate to facilitate a webinar for the children or grandchildren of clients on a specific financial planning topic;

- Tasking the associate to solve a client challenge or handle a service issue;

- Asking the associate advisor to share insights about how to respond to clients. For example, when a client emails that they feel nervous about market drops, the senior advisor can discuss potential responses with the associate and then respond to the email with the associate carbon copied. The initial response from the senior advisor can include the client’s concern, and then the associate might send an additional follow-up note including helpful information for the client (e.g., a graphic showing historic market rebounds after declines or their take on what’s happening);

- Letting new clients know up front, during onboarding, that work is done as a team and that the associate advisor will serve as their primary point of contact;

- Encouraging the associate advisor to reach out to top clients for milestone events (e.g., birthdays, anniversaries, and achievements). Outside of the traditional milestones, associates might also reach out to the client for other meaningful occasions like a child’s graduation, the birth of a grandchild, or even hitting a savings or budgeting goal; and

- Supporting the associate in emerging as a thought leader by providing the resources for them to start a blog or a video series, where they address common client financial questions and concerns.

As associate advisors gain experience, their skills and expected responsibilities will increase over time. They may be allowed to take a lead role in meetings and conversations when onboarding a new, smaller client, with the senior advisor sitting as second chair. The associate advisor might also be introduced to lower-tier relationships, paving the way for them to take a lead role in facilitating client reviews.

The following graphic illustrates an example of how metrics can be organized to help senior advisors determine when associate advisors might be ready to advance to greater responsibilities.

Updating Associate Advisor Objectives And Key Results (OKRs)

Eventually, the associate advisor will have completed 3 phases of development:

- Observing other advisors;

- Practicing skills in a controlled environment with immediate feedback; and

- Leveraging their skills independently.

Over time, as the associate advisor develops and their OKRs are reviewed and reset through quarterly reviews, their long-term career path will become clearer based on their proclivities and strengths. They might develop into an advisor who can focus on new business development, or they might become an advisor with the ability to manage 80 to 100 relationships in the business. Either way, the time spent training the new associate will have been well-invested in creating a valuable asset for the growth of the firm.

When it comes to reviewing OKRs, there are a few things to consider. First, OKRs should be set at the beginning of the year and should be reflected upon, but not changed, on a quarterly basis. Associate advisors (and all team members) should be expected to attend quarterly reviews of their OKRs and to share their insights around their progress using key results as benchmarks. For example, an associate advisor might say something like, “One of my objectives is to create capacity for you during the week. I have made progress in that area by handling pre-work for you and getting you prepared 2 days in advance of meetings, but I am struggling with doing the follow-ups on my own. I feel like I keep needing to come to you for help.” Senior advisors can be especially helpful by spending time troubleshooting any pain points that come up for the associates.

When resetting OKRs for the following year, one strategy is to make minor tweaks and adjustments to the OKRs that associate advisors have been tracking already, potentially by adding new key results. If there hasn’t been a material change to the associate’s role, and they are continuing to shadow, develop, and learn from the senior advisor, then changes may not be necessary yet.

For example, an associate advisor who has been performing well and has exceeded expectations during their first year has handled follow-up tasks and prep work efficiently and has acclimated within the team with a solid understanding of the firm’s story. However, they still need time to develop their communication and presentation skills. After year one, the OKR to build rapport with clients, as presented earlier, might be adjusted as follows:

- Objective: Build rapport with current clients.

Key Result 1: The associate advisor is always aware of critical information about a client before meeting or speaking with them, including any special preferences the client has.

Key Result 2: The associate advisor stays present with clients by communicating with them on an ongoing basis (e.g., providing topical thought leadership content and choosing clients randomly for weekly check-ins.)

Key Result 3: Except for the clients we have identified as ‘not ready’, all lower-tier clients’ questions are handled by the associate advisor rather than by the senior advisor.

Key Result 4: The associate advisor is consistently seeking new information about a client during each meeting and adding those notes to CRM.

Notably, Key Results 1 and 2 remained unchanged. However, to help them focus on improving communication and presentation skills, Key Result 3 was modified to clarify the particular clients the associate advisor would be responsible for, and Key Result 4 was added to help the advisor focus on developing a deeper understanding of the clients and their issues of concern.

For associate advisors with material changes to their role or who have developed to a point where they are fully handling client relationships, then there might be additional Key Results tied to their elevated role. For example, in the previous OKR discussed earlier, addressing the exceptional service that clients receive, Key Results 4 and 5 were added to the advanced associate advisor’s updated OKR.

- Objective: Provide exceptional service to firm clients and deliver on the firm’s value proposition.

Key Result 1: The associate advisor will respond to all client emails within an hour and to all client phone calls by the end of the day, even if they don’t yet have an answer for them.

Key Result 2: The associate advisor will provide clients with a summarized follow-up to all conversations and meetings within 24 hours.

Key Result 3: The associate advisor will ensure that all clients with unresolved questions receive an update on the status of those items before the close of business each Friday afternoon.

Key Result 4: 99% of clients directly managed by the associate advisor are retained by the firm.

Key Result 5: Clients never need to ask for a review meeting because their expectations for service have been set for the year.

It is important to note that individual role OKRs are easier to craft and adjust after annual team meetings that discuss goals and objectives for the following year. Framing OKRs as a firm first can help advisors determine what their own OKRS should be. This is especially true for firms that are growing rapidly or that are in the process of implementing major new initiatives at the firm.

For example, a senior advisor who plans to transition all “C” clients to their associate to handle annual reviews might set a new objective as, “The associate advisor will deepen relationships with C clients.” Their key results might center around moving the “C” clients to the firm’s new subscription model and transitioning them to a new service model.

On the other hand, a new objective for the senior advisor could include “To fill additional capacity with revenue-generating activities.” The key results would then center around how the objective would be achieved. For example, generating a new blog each week, landing a speaking engagement each month, or asking for referrals from several households each week.

Telling Clients About The New Roles And Expanding Firm

Another notable point about the associate advisor’s development and growing role in the firm is the importance of communicating to clients about who the new associate is, why they have been added to the organization, and what the long-term plan is for them. Clients appreciate being kept up to date on how the firm is doing, and senior advisors can keep them posted by routinely communicating about the overall health of the business by sharing their efforts to grow the team and the firm’s capacity to serve more clients.

By doing this, senior advisors prepare their clients for the reality that, one day, they may be served by a different advisor at the firm. Sending a letter to all clients at the end of the year or offering some thoughts at an upcoming client event can be good ways to share the news. The messaging might go something like this:

We’ve been doing a lot of reflecting about the last 2 years. We recognize how important it is to continue to do the work that we do, helping families plan for the future and navigate life’s difficulties. To continue providing the same high level of service that we’ve always offered, we will be growing our team this year and adding associates to our organization. These are professionals who are on a pathway to becoming Financial Advisors and who will assist us in providing a deeper level of service to you. You’ll get to meet our newest associate at your next review, and you may be hearing from them soon via email!

Designing Compensation Models Based On Firm Goals Can Work Better To Incentivize Next-Gen Associate Advisors

There are varying opinions on how to compensate associate advisors within a firm. As discussed earlier, because the producer model is still prevalent in our industry, there are many associates being compensated with small salaries (or draws) and large incentives tied to individual production (i.e., bringing in new clients/new assets). Not only does this structure tend to be a poor driver of associate advisor behavior (especially when it comes to next-gen advisors), but it also makes several assumptions about the associate advisor that we already know are likely not true (e.g., that they will be employees who want to and have a skillset to be prospecting and bringing in new business immediately).

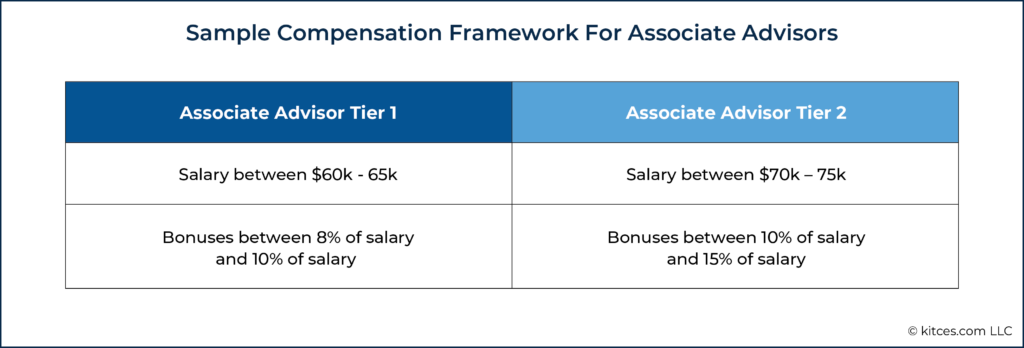

A better strategy to compensate next-gen associate advisors in a more meaningful way can involve salaries with bonuses tied to firm goals, rewarding them for working effectively with the team and keeping everyone rowing in the same direction. The salary-plus-bonus structure is ideal for next-gen advisors because it aligns with their natural affinity for working in teams, ensuring that they have time to develop and mature within a collaborative environment.

Associate advisors might also have a third compensation component, in addition to their salary and firm-goal-based bonus, comprising an incentive structure tied to qualitative metrics assessing their own performance, such as how much capacity they have created for others on the team or their level of engagement in client relationships.

These qualitative metrics can be tied directly to OKRs, providing the basis for the associate to determine whether they are on track to earn additional incentives or not. Theoretically, quarterly reviews should offer enough time and space for both the senior and associate advisor to discuss their progress and performance and to collaborate on how to support each other in achieving objectives if they aren’t already doing so. Which is why discussing real-time feedback is so critical – they help everyone understand how to participate in the team’s success and how to earn extra incentives (which could be monetary but don’t have to be) for being accountable and responsible for performing in their role, based on OKRs that both the associate and senior advisor have discussed and agreed to.

When deciding how much to compensate the associate, industry compensation studies can offer good guidance. For example, the 2020 Comp & Staffing study from Investment News indicated that junior advisors’ median salary and bonus in 2020 were $65,703 and $6,000, respectively.

Prior to hiring the associate advisor, leaders should create, for themselves, a framework for what compensation could look like based on the tenure of the candidate, as well as the firm’s own P&L figures and goals. For example, senior advisors might consider a structure such as the following when thinking about the evolution of an associate’s compensation:

Rather than presenting the bonuses as a percentage of salary, senior advisors might consider presenting the bonus as a number simply to make the actual bonus amount less confusing. For example, $6,000 will be paid out half at the mid-year point and the other half at year-end.

If leaders want associate advisors to have ‘skin in the game’, they could also consider paying out the bonuses on a sliding scale, contingent on the percentage of goals the firm hits with a given cap (e.g., 110%). This method ensures that there is total transparency around compensation and that the entire team is working together to achieve goals and compensation (which also requires leaders to be incredibly clear on firm goals!).

In terms of long-term compensation, senior advisors might opt to adjust the design of bonus structures for associate advisors after they have had time to develop and choose a path within the firm. Advisors can have this conversation around the 3-year mark, although the timing might be sooner or later, depending on the associate’s development. At that point, it should be clearer to both leadership and the associate whether the associate will develop into a lead or senior advisor responsible for delivering complex advice (a mostly salary-based role) or into an advisor who primarily develops new business, giving them an opportunity to earn larger bonuses and incentives.

Ultimately, the associate advisor role is critical for any team looking to grow or scale. Finding and developing an associate advisor is no easy task, however, and firms must put much thought into how they will integrate the person into their firm and culture and how to develop them over an extended period of time.

The transfer of relationships from senior advisor to associate advisor does not happen overnight and will require a lot of time and partnership over a series of many years, especially if the associate is a next-gen advisor who is greener to the business and hasn’t had time to develop and hone their advising skillset.

Advisors looking to hire associate advisors or to reimagine a role that exists on their team can focus on the following key points: Make sure everyone on the team has a solid understanding of the associate advisor’s role, including the purpose of having one on the team, the impact it should have on the business, and the long-term alignment to the vision for the practice. And while there may be many best practices on this subject, advisors should feel free to get creative with designing their associate advisor roles, as taking a slightly different approach might actually work very well to help make progress towards scaling the practice!